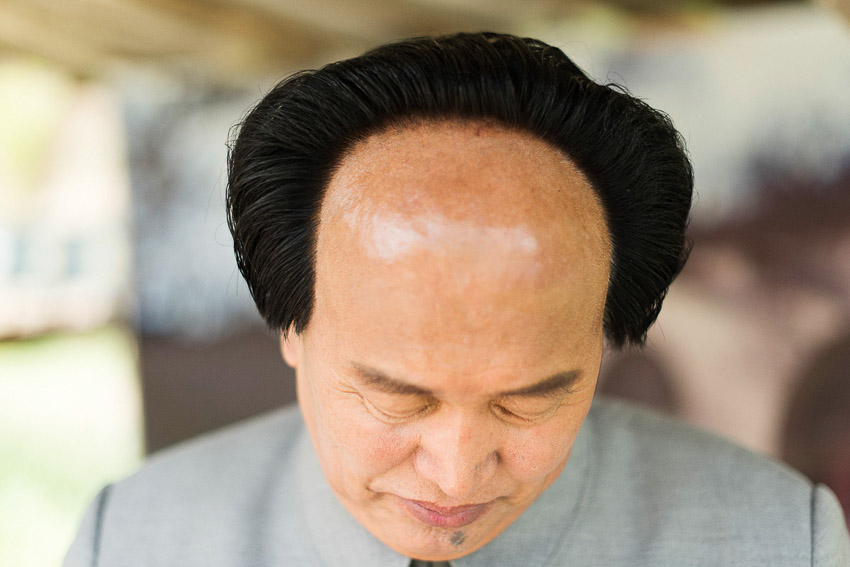

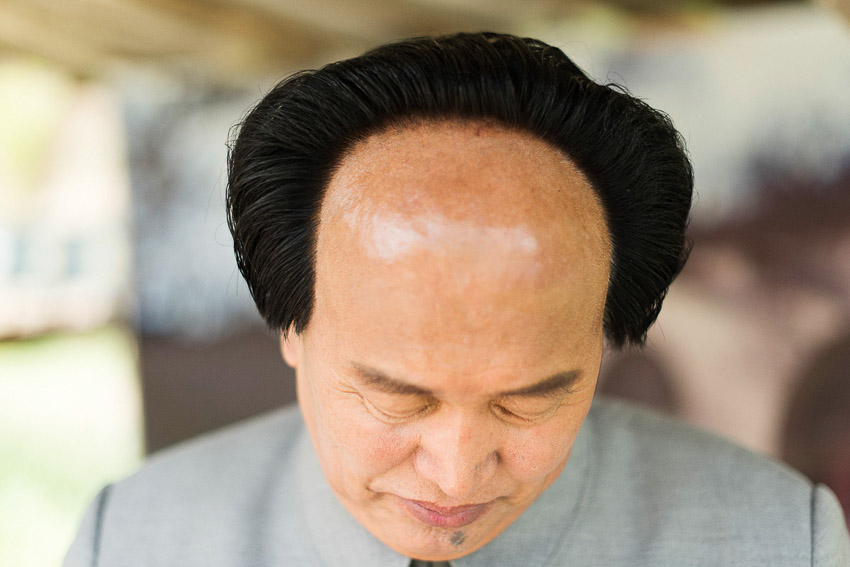

Before long, the Chairman had seeped into every aspect of Yan’s daily life—“I watch my words and behaviors at all time and places”—hijacking his mind. When he traveled to Hunan, where Mao was born, after painstakingly mastering Mao's thick southern accent (Yan is from northeast China), the crowd around him fell to the ground, kneeling and dragging his legs, refusing to let go. “He’s beyond a great man or an idol in my heart,” Yan explained. “He is a god.” In the past decade, religion of all sorts has experienced a renaissance across the nation, and the Chairman, arguably secular China’s most sacred figure, has been no exception. The original Mao has remained a crowd-pleaser: every morning a line of pilgrims snakes around Tiananmen Square’s mausoleum, dutifully shuffling their way towards the leader’s remains (still in his gray suit). Last year, when the People’s Republic reached the fiftieth anniversary of the Cultural Revolution, which brought the persecution of millions of citizens, Mao Zedong was everywhere and nowhere. Caught somewhere in the paradox of amnesia and nostalgia that is modern China, the father of the nation is still iconic. (In official documents, he is remembered as 70% good, 30% bad.) While the Chairman is only briefly touched upon in history classes, Mao-mania is present in contemporary art and pop culture. There are temples to worship the deceased leader, and “Red Tourism”—revisiting China’s revolutionary past—has become a lucrative industry. And now there are an estimated tens of thousands of Mao impersonators nationwide, devoted to resurrecting the leader. Text by: Kim Wall